Bees see the world in vibrant color…but that may be changing. Smithsonian-Mason team researches the impact with bee vision.

When a bee sees a flower, it knows where to land thanks to its ability to see ultraviolet (UV) color patterns on the petals. Many factors have caused those colors to dull, and now a team at the Smithsonian-Mason School of Conservation (SMSC), funded by a grant from the National Geographic Society, is helping reveal what pollinators see, and why it matters for the future of conservation.

Pollinators and Color

Honeybees help pollinate plants that produce food; they also help maintain biodiversity. That’s part of why understanding how they interact with plants matters.

“Pollinators make really important decisions about colors all the time—and those colors are changing [due to climate change, changing pH levels and changing temperatures],” said Daniel Hanley, a George Mason University professor and National Geographic Explorer who is Siegle’s research mentor.

The research findings could also help the team uncover which flowers may be beneficial for pollinators to have around, or what could be done to ensure wildflowers aren’t being impacted further, Siegle said.

Among the Flowers

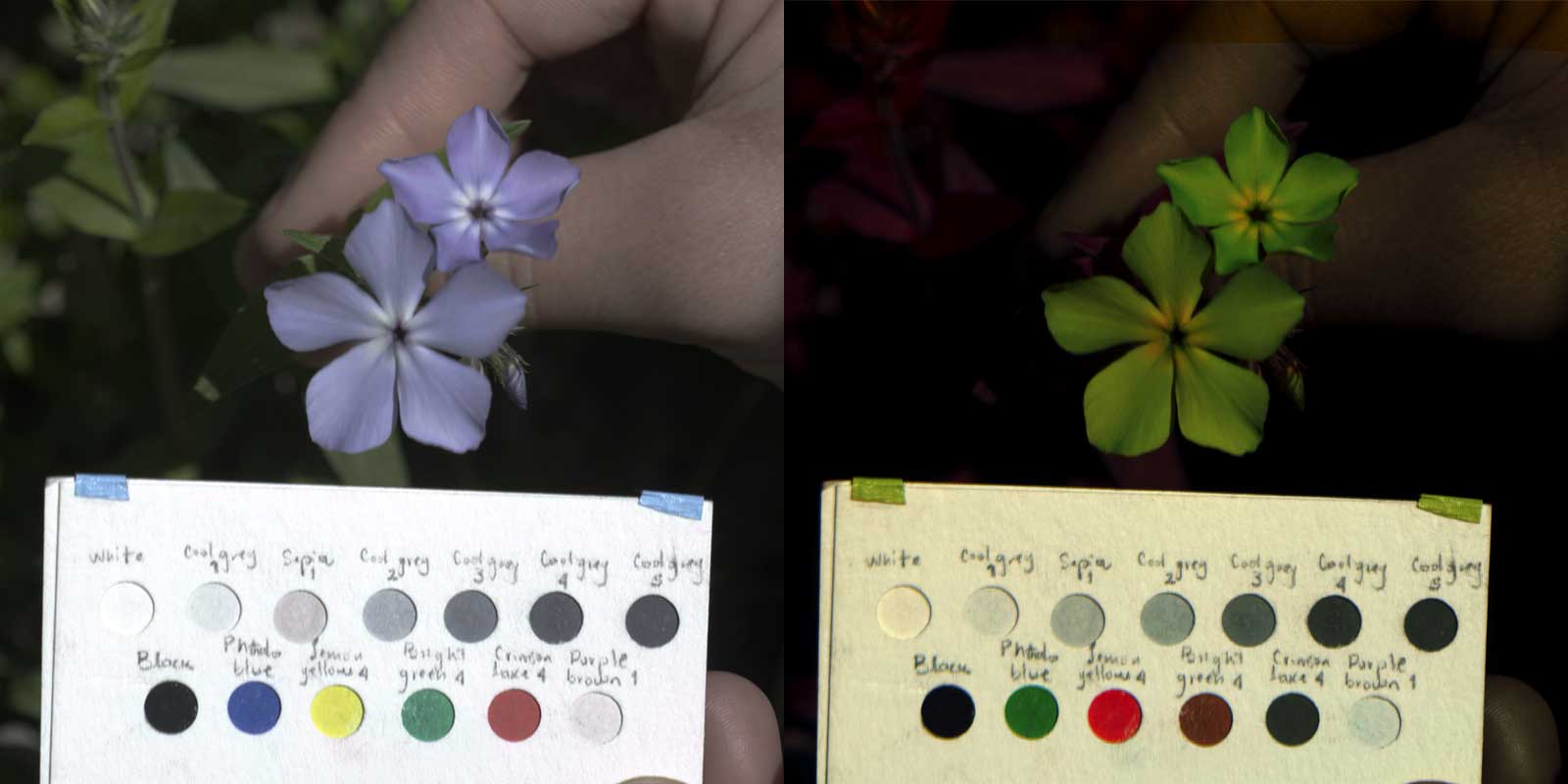

Exploring how pollinators perceive color requires precision and technology, as UV colors are invisible to the human eye.

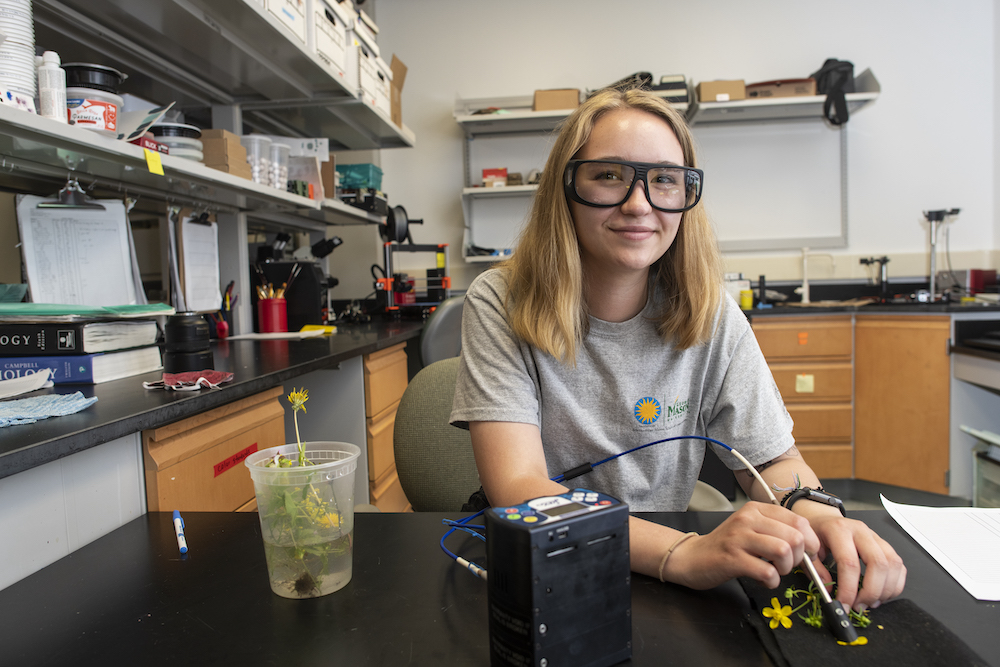

Siegle’s work begins with photographing, recording, and measuring flowers. She uses a multi-spectral camera that films both UV and visual light, and calibrates the camera for color precision and accuracy using color and white standards.

Using a spectrometer and spectroradiometer, Siegle also measures the reflectance of each flower and the color of the light. Later, she brings these data to the lab for analysis and processing. With the help of Python computer code, the photos are transformed into images of what a honeybee would see.

Colors Lead to Answers

Hanley described his lab’s focus as primarily gathering information about how pollinators see and how perceived color diversity is quantified.

“This eventually will help us address why colors might be changing over time and how,” Hanley said. “It also helps us understand what the bees are actually paying attention to, and how it helps them with their interaction with the flower, which is critical for pollination.”

Siegle’s research is expected to have ripple effects.

“We’ll be able to see how bees are orienting to those visual signals in a way we hadn’t really been able to do before,” Hanley said. “That can be used for answering all sorts of other questions not just for pollinators, but all sorts of organisms that are using color.”

The imagery Siegle creates for the project will also be used to help bring the science to life with multimedia, including documentaries and films, she said.

Hands-on Conservation

Mason was the only school Siegle said she applied to, and SMSC was her top reason for applying.

“I have been waiting for a few years to attend SMSC,” said Siegle, who aspires to work in elephant conservation.

“It’s been amazing,” she said. “The classes have been really interesting, I’ve learned a lot, had a lot of hands-on experience, and made a lot of connections with the professors, other conservationists and guest speakers.”

It’s likewise rewarding for the mentors.

“It’s been really cool to be able to work with a student for weeks at a time to really dig into a problem,” Hanley said. “[At SMSC] you can invest in yourself and your development as a scientist in a way that other students really may nothave the chance to.”

Related News

- June 13, 2025

- April 4, 2025

- January 29, 2025

- November 8, 2024

- October 7, 2024